In the series of events that occurs in order for us to obtain our daily cup of coffee, the processing stage is one that has lately been at the forefront of the world of specialty coffee. While it’s always been a necessary step in the coffee production chain, new and exciting processing methods have been emerging left, right, and centre as ways to elevate that daily cup of bean water. Ever looked at a bag of coffee and wondered what lacto-fermentation is? How about carbonic maceration? Because this overload of new techniques can be overwhelming, we at Doorstep Barista thought we would break these all down for you so you know exactly what you’re sipping on when you open your Doorstep box every month. This month’s blog post will start with the three most common processing methods, and next month will focus on those fancy schmancy other ones.

So, to begin: what is processing?

Processing refers to the stage in coffee production where the coffee cherry is removed from the pit—which is actually the green coffee bean!— and the green bean is then dried. Variations in processing methods generally occur in terms of how and when the pulp is removed from the bean, and how the bean is dried, all of which affect the final flavour.

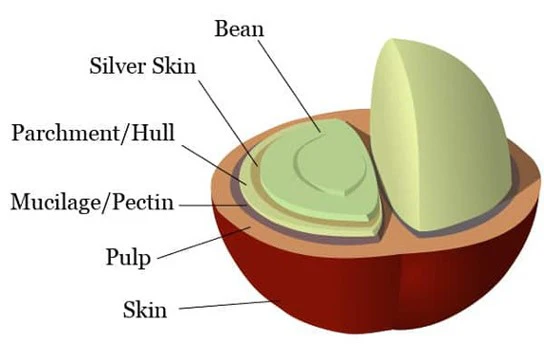

The next thing to know before jumping into processing methods is the parts of the coffee cherry. The cherry is formed of several layers (illustrated below) and these are the specific parts we will be referring to as we go through the different methods.

And now, we turn to the three most common processing methods!

Natural (or Dry) Process

After the coffee cherries are harvested, they are laid out to dry, either on the ground or raised beds. Over the course of up to 6 weeks, the cherries are regularly turned to prevent rotting while still allowing for fermentation as the pulp imparts its sugars and fruit flavours to the green bean. Once dried completely, the skin, pulp, mucilage, and parchment/hull are removed, and the green bean is ready go.

There are several advantages to the natural process. First is that, for the producer, this is an especially accessible method because it requires no special machinery or facilities, and, in drier countries, works conveniently with the climate. It can also produce exceptionally fruity and complex flavours in the final product, and a wider range of flavours.

But there are also disadvantages: the fermentation process puts the bean at a higher risk of molding and developing defects, making it less appealing for a farmer or producer to want to put so much at stake. Additionally, it can be hard to replicate a specific flavour profile from harvest to harvest. Some people also don’t like the fermented flavours that can develop, sometimes referred to as a “barnyard” taste.

Washed (or Wet) Process

The main difference between the natural and washed process is that the washed process removes the pulp and mucilage from the bean BEFORE drying the green bean. After being picked, the cherry is depulped, leaving just the mucilage. To remove the mucilage, the bean is placed in tanks of water, creating an environment where the mucilage is eaten away by naturally present bacteria over the course of a couple days. The bean is then rinsed of mucilage, dried in raised beds or mechanically, and then dry-hulled to remove the final parchment layer.

Since producers have greater control over each variable in the washed process, flavour profiles are easier to replicate and there is lower risk of defects in each batch. People enjoy the clean, bright, and light-bodied flavours that are often (but not always) representative of washed process beans. On the flip side, washed processes require specific facilities and equipment, and large amounts of water, which can be very costly for farmers.

Honey Process

This process is often described as landing somewhere between the natural and washed processes. Like the washed process, the cherry is depulped after being picked. But, instead of removing the mucilage, the bean is both fermented and then dried with the mucilage still intact. After the drying, the bean is dry-milled to remove the remaining layers of mucilage and parchment.

There are several types of honey process: white, yellow, red, and black. The colour refers to the amount of mucilage that is left on the bean after being depulped; white honey process means there is very little of the mucilage left, with the mucilage levels increasing all the way to black honey, the process that utilizes the most mucilage. Some growing regions use white, yellow, red, and black honey process to refer to the amount of time the sugars caramelize for during fermentation (the longer they ferment, the more they caramelize, the darker in colour).

While the honey process uses less water than the washed process and requires less equipment, it does carry higher risk of defects, just like the natural process. People enjoy honey processed beans for their unique, fruity, and complex flavours, while still maintaining crisp and clean aspects of washed process beans.

Okay, that was a lot of information.

But hopefully now when you look at a bag of beans and see the processing method indicated, it all makes sense! And now that we’ve covered the basics, we can look at some more complex processing methods. Stay tuned for next month’s post where we’ll do our best to explore the more complex processes being introduced to the specialty coffee world.